This article is to honor Colonel Alan J. Rubin.

But first the backstory.

In the summer of 1979, I worked as an armed guard at a high rise in Denver. I noticed haggard young lawyers leaving the building late each night. When I finished law school four years later, I did not want to be one of them, so I joined the Air Force as a legal officer. I hoped to see the world.

The Air Force sent me to Nebraska – the state next door. To Offutt Air Force Base, south of Omaha. My first boss at Offutt was Colonel White (not his real name). He was flamboyant and seemed like a God to me, a young lawyer with no legal or military experience. There were usually seven or eight young lawyers assigned to the legal office. We often ran as a group, and the unwritten rule was that nobody ran ahead of Colonel White. If he had to go somewhere, he frequently took one of us with him. We called it, “aide duty.” After about two years, the Air Force reassigned him to the Pentagon. We knew Colonel White and shared anxiety about his replacement.

Colonel Rubin was a bull of a man. A Vietnam vet, he was short, but powerfully built. His balding head seemed to always be a tad in front of his body because he was always on a mission. The Air Force thought highly of him and appointed him as a military judge – a duty he performed for eight years. He was the most direct person I’ve ever met. We took one look at him and thought, “Well, the good times with Colonel White are over.”

When Colonel Rubin became the Staff Judge Advocate, his first act was to gather everyone in the courtroom and announce some changes. One thing that stands out was, “I want every sign and every poster in a frame. If it’s not in a frame, it’s coming down at 5 p.m. tomorrow.” Much later, he told me, “Whenever you assume a leadership role, make your changes right away. Don’t try to win friends by gradually implementing them.”

When we ran as a group with Colonel Rubin, it was fine to run ahead of him. “You’re twenty years younger, you’d better be faster than me.” One time he announced he was going to the other side of the base for something and I asked if he wanted one of us to come along. He got a quizzical look and I explained how Colonel White had often required one of the young captains or lieutenants to accompany him. He snickered and said, “I don’t need a f****** aide.” (Not his actual words). “The Air Force isn’t paying you to follow me around. Stay here and do something useful.” And through these experiences I gained a better understanding of leadership. He told me, “This job is easy. Just do whatever is in the best interests of the Air Force.”

Colonel Rubin and I had much in common. We were both raised Jewish. We both left Judaism after our bar mitzvah. We were both born on the east coast and moved west when were young. We were both single.

And we both had a sense of humor. Every seven or eight weeks one of us young officers assumed the rotating duty of “On Duty JAG,” which meant carrying a beeper and being available 24/7 to respond to legal questions from the base commander or the Security Police. One night I phoned Colonel Rubin and said, “Sir, we have a situation. The Security Police were conducting a drug detection operation at the main gate and the dog alerted on General Smith’s vehicle. Do you want me to terminate the operation?” General Smith (not his real name) was the four-star general in charge of the Strategic Air Command.

Colonel Rubin said, “Cone, I want you to crawl back into bed with whatever skank you managed to drag home tonight, and we’re going to forget this phone call ever happened.” Click. He always called me, “Cone.” Because why use two syllables when one would do? That was Al Rubin.

In the Air Force, as in many organizations, the younger staff people draft the letters and documents that the more senior people must sign or approve. I thought I wrote well, but whenever I submitted a draft to Colonel Rubin, he would summon me to his office and hand me a copy of my draft that he had marked up with his red pen. “Whose version is better?” he would ask. His version was better. Every time. He improved my writing immensely.

Colonel Rubin enjoyed teaching the young lawyers under his command. He made us all better. He was one of the most organized people I’ve ever met. He had written standard operating procedures for everything. He also understood the importance of being able to find information quickly. In a trial that is vital for a lawyer. I was honored when Colonel Rubin asked me to coauthor an article on trial preparation and organization. He later put me in charge of military justice at the base. I was twenty-seven years old and essentially deciding who would get court-martialed and who would not. (Colonel Rubin could have overruled me, but never did).

I remember prosecuting one case and Colonel Rubin summoned me to his office. He said loudly, “Why is case taking so long? What the f*** is this judge doing? As a judge, I could have completed this case yesterday.” I put my finger to my lips, pointed to his office door, and said, “Sir, the members of the court martial (jury members) are right outside your door.”

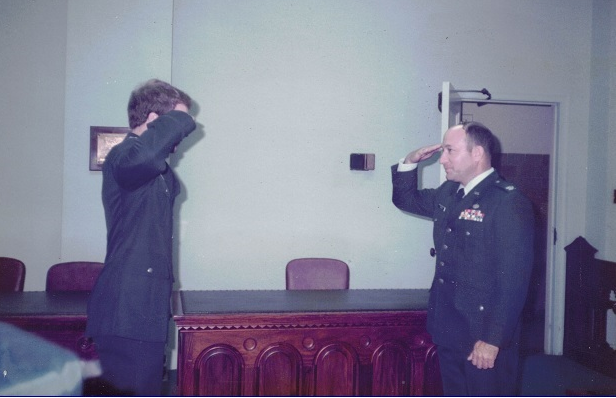

Within a year of Colonel Rubin’s arrival, I saw how his leadership had transformed the base legal office into an efficient, professional operation. Although he was tough as nails, Colonel Rubin strived to be fair. There was an incident in which a young NCO had shaken his baby to death, and I wanted to send the case to a general court martial for murder. He called me to his office and asked me if that would be the right outcome. He wanted to be sure it had not been an accident. I laid the case for him, and he approved it. Partly because of my success in that case, in 1986, the American Bar Association named me the Outstanding Young Military Service Lawyer for that year. Colonel Rubin was so proud that one of “his people” had received this honor. And he was genuinely happy for me.

Colonel Rubin had a sensitive side. Most lawyers enter the Air Force with a reserve commission, and to make it a career a young lawyer had to apply for indefinite reserve status. The Staff Judge Advocate had to recommend whether to approve those applications. In one case, Colonel Rubin recommended against approving that lawyer’s application. He had tears in his eyes, but he felt that’s what was best for the Air Force and for the lawyer.

Al Rubin enlisted in the Air National Guard after law school and told the personnel people (he called them “personnel pukes”) he would do anything that did not involve seeing blood, so they made him a flight medic. He passed the Arizona bar exam in 1963 at the age of twenty-three, and became the youngest lawyer in Arizona. He practiced criminal defense law in Phoenix. Practicing law as a solo lawyer is not easy, so Al Rubin entered the Air Force JAG corps in 1966 and soon found himself living at Cam Ranh Bay in South Vietnam.

This article would not be complete without telling the story of how Al Rubin, who was a bachelor until age 44, met his beautiful wife, Fran. In 1972, Fran was married and was a civilian Air Force employee of the Air Training Command at Randolph Air Force Base in Texas. They met at a conference. Everyone was looking for Al, but he was playing golf with a general. He returned to the conference in golf clothes while everyone else wore their dress uniforms. Fran caught Al’s eye and a few weeks later he called and he invited her to come work for him at Williams Air Force Base. He did not know that everyone else in Fran’s office was listening to their call. Fran told him she was married and said, “Goodbye.” Ten years later Fran was single and Al became the Chief of Military Justice for the Air Training Command at Randolph AFB. Someone introduced them and asked, “Have you two ever met?” Fran instantly said, “Yes,” and Al simultaneously said, “No.” They married in 1984.

I left active duty in 1987, and Colonel Rubin retired that same year. We stayed in touch, and later he and Fran donated money to us so we could adopt our children. He retired to Florida where he enjoyed scuba diving, golf, and re-upholstering vehicles. He loved cars and even had a Rolls Royce.

Al Rubin died on March 21, 2022 at the age of 82. It was a surprise because he was in good health and had boasted a resting pulse was 62.

Al Rubin was a Republican, enjoyed talking politics with those holding different views. I never had the heart to tell him I had Bill Clinton’s office at the University of Arkansas School of Law when I taught there in 2013-2014. After his death Fran joked, “At least you didn’t have Hillary’s office.”

When I think of Al Rubin, I think of the theme song from Blazing Saddles. “He rode a blazing saddle, he wore a shining star, his job to offer battle, to bad men near and far. He conquered fear and he conquered hate, he turned dark night into day; he made his blazing saddle a torch to light the way.”

And, for the record, this article reads at a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 6.9 and contains zero percent passive voice. Thank you, Colonel Rubin.